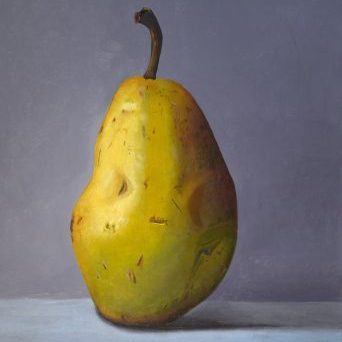

Pear #101, Rose Pear, 20" X 18" Oil on Panel

This study examines a hyper-realistic painting of a solitary pear through the lens of formal artistic analysis and symbolic interpretation. The painting, marked by its meticulous attention to detail and restrained composition, evokes a contemplative atmosphere, inviting reflections on transience, natural beauty, and the aesthetics of imperfection. The analysis considers compositional elements, chromatic schemes, texture, and light to understand the broader implications of this seemingly simple still-life subject.

Introduction:

Still-life painting has long occupied a significant place in the Western art tradition, functioning both as a celebration of the quotidian and a memento mori. The subject of the pear—rooted in symbolism, biology, and aesthetic tradition—offers fertile ground for interpretative engagement. This paper focuses on a contemporary pear painting that exhibits qualities reminiscent of 17th-century Dutch still-life yet reframes the subject through a modern minimalist lens.

Visual and Formal Analysis:

The pear, centrally positioned and vertically dominant within the composition, is rendered with photorealistic precision. The background, a muted and homogenous plane of matte grayish lavender, subtly isolates the subject, emphasizing its material form. The surface on which the pear rests is a cool-toned gray, contributing to the overall subdued palette and enhancing the tactile realism of the fruit.

The artist employs chiaroscuro techniques, casting a soft shadow to the lower right, which enhances the three-dimensionality of the form. The light source, likely frontal or slightly lateral, accentuates the skin’s topographical features: natural bruises, blemishes, and subtle color gradations ranging from golden yellows to russet reds. These imperfections elevate the painting beyond idealized representation, inviting an appreciation of organic authenticity.

Symbolic Interpretation:

Historically, the pear has symbolized abundance, fertility, and the ephemeral nature of life. In Christian iconography, it has also represented divine sustenance and maternal nurturing. However, in this work, the pear’s slightly bruised, asymmetrical form introduces themes of aging, individuality, and impermanence. Rather than idealize, the painting embraces natural irregularity, prompting a meditation on wabi-sabi—the Japanese aesthetic of imperfection and impermanence.

Moreover, the solitary nature of the fruit, devoid of human presence or accompanying objects, fosters a quiet, almost sacred stillness. This compositional restraint directs the viewer’s focus inward, transforming the pear from a mere fruit into a vessel for existential contemplation.

Conclusion:

This pear painting transcends its subject through a compelling integration of technical mastery and symbolic resonance. In its stillness and solitude, the work elicits reflections on the nature of time, beauty, and being. It reaffirms the power of still life to engage viewers not only visually but philosophically, elevating the mundane into a space of profound introspection.

References:

Bryson, N. Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting. Reaktion Books, 1990.

Alpers, S. The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century. University of Chicago Press, 1983.

Juniper, A. Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence. Tuttle Publishing, 2003.